Pooling data from Roman regimes, classical Mayans and Anasazi shows the same pattern as Lower Mesopotamia. Also, Egypt shows the same pattern except that there is selection at work early in the course of regimes, and a few regimes escape the brick wall crushing Mesopotamia.

I was showing you the time course of collapse of civilizations (regimes, empires, what have you) in lower Mesopotamia. I also pooled the experience of Rome, the classical Mayans and the Anasazi. Rome was a bit tricky, since it survived for a long time in name while the ruling powers changed from time to time. For instance, the first rise of the emperors I considered a change. I drew the information from the BBC. I don’t have my source for the classical Mayans, but it appears that they went through about three clear cut changes. The Anasazi are now called the “ancestral Pueblos,” but I am a bit uneasy about that term. I certainly accept that they were related to modern Pueblos, but whether the ancients that are studied actually have modern descendants is problematic. If my records serve, I drew from The Collapse of Complex Societies.

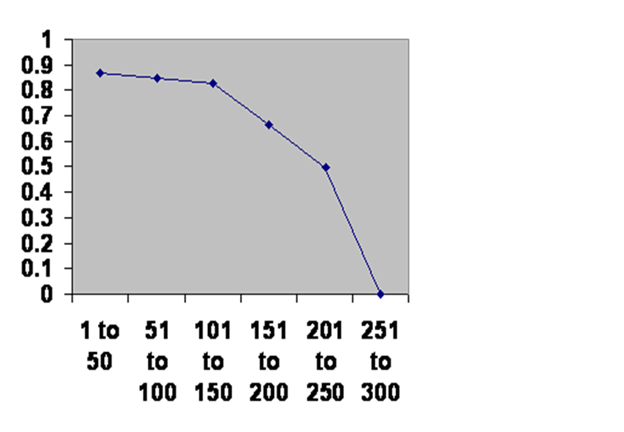

As before the age of each regime when it fell is on the horizontal axis in 50-year increments. The vertical axis is its chance of surviving the next half century after it has entered that half century. If death came from outside, the viability of a regime would have nothing to do with how long it was since it was founded, the line would be horizontal. If regimes differed significantly between populations, there would be selection and regimes that had lasted longer would continue to last longer; the line would rise. But the line again falls.

As before the age of each regime when it fell is on the horizontal axis in 50-year increments. The vertical axis is its chance of surviving the next half century after it has entered that half century. If death came from outside, the viability of a regime would have nothing to do with how long it was since it was founded, the line would be horizontal. If regimes differed significantly between populations, there would be selection and regimes that had lasted longer would continue to last longer; the line would rise. But the line again falls.

Fig. 33 13, 14

Chew on it. The line is clean as can be, so only one process or two must be a work knocking down these regimes. There is the same 300-year brick wall, so it must be the same mechanism. And the line goes down proving that the effective mechanism is neither within the population nor outside the population so it has to be the very fact of a population that is big enough, or an administrative class that is big enough, to serve the needs of a civilization.

I concede that there is a bit of overlap. The Romans did indeed once rule Mesopotamia, so they potentially figure in both graphs; knowing whether that is true would require more historical savvy than I have. A professional historian ought to be able to tell, but I have been unsuccessful in getting any expert to take an interest.

That simply overwhelms me. How any expert could look at this unmoved is baffling. It’s as if you were to spend your life looking at the mouth of a cave and watching what came and went. If a sheep goes in, a lot of roaring comes out but no sheep. Bats come and go. Bears come and go with the seasons. And then somebody tells you how to enter the cave safely and look around. It ought to be irresistible.

In fact, I don’t know how anybody could fail to be captivated. If I might digress with a little personal history: I have always dreamed copiously. When I was young my dreams were sweeter than they are now. I won’t complain; the frustrations in the dream are not so intense as the frustration of doing what I am now doing in vain. But the sweet dreams of youth do not return.

A down side of such dreaming was that I would awaken and yearn to return to the dream. Well and good; I’m sure such things are not rare. But sometimes the same wistful yearning would strike me when I was wide awake with no dream being remembered. I asked my parents what it was. I don’t think they understood any better than I do now. I assumed it was a fancy of youth, and I would outgrow it, but middle age arrived and I still occasionally would feel it, sometimes when I was quite preoccupied with things of immediate importance.

I suspect poets have described it, Victorians mostly, including Edgar Allan Poe. But I have never known a word for the feeling. It was like I was homesick for something that had never happened. It was not unpleasant and was easily shrugged off, but it was an enduring feature of my inner landscape.

I happened to become involved in the issue of the health of US veterans. That deserves a book all on its own except that it is not obviously related to the issue of the mechanism of inbreeding and outbreeding depression … well maybe don’t you know? … I mean if nature expects us to live in communities of a certain size and make-up … and if we don’t it might make us unhappy. Sorry I can’t lead you to that with iron clad logic nor articles in prestige science journals … but maybe.

Moving back toward topic, putting somebody into combat is a horrible thing to do to them. The day came when we went to war in Iraq. Saddam Hussein had asked the US ambassador whether it would be all right to take the Kuwait oil fields. The US had been trying to get permission to put up a military base in Kuwait, but had been rebuffed so instead of saying, “Try it and we’ll blow you to smithereens,” the American official said, “Arab borders are Arab business.” Kuwait was overrun. The US moved troops into Saudi Arabia and then on a day invaded Kuwait to drive Iraq out. At least that’s how I remember it, which is my point. The truth of matters I am happy to leave to others.

So, I literally was lying on my couch thinking, “This is an unnecessary war, and they know perfectly well how terrible war is for all concerned. WHY? Why do people choose leaders who act upon the hatred of outsiders that normal people only mutter about? Why such hatred in the first place? There must be a selective advantage to it. It has to be biological.

“Maybe societies, biggish ones, get unstable simply because of their big and diverse mating pool. How long does a society last anyway? Is there a clue in that?”

I put together the numbers I showed you for lower Mesopotamia. The graph you have seen became the whole focus of my life.

Emotionally I have never recovered. Those sweet wistful dreaming moments vanished altogether. Nothing was left but the burning need to warn the world.

So how anybody can look at either of these graphs and then forget about them escapes me.

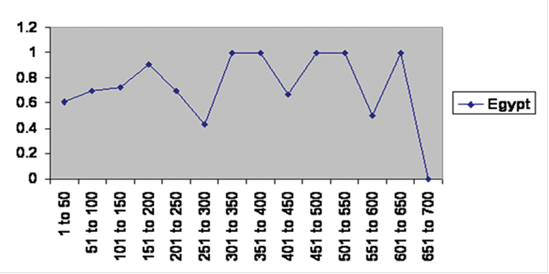

Now consider Egypt.

Here is the survival experience of Egypt. Same coordinates. The vertical axis is the chance that a dynasty of that age will survive another 50 years. The horizontal axis is the ages of the dynasties.

Fig. 34 15

You recognize the coordinates (survival as a surrogate for young people against time) of the Mesopotamian graph quite different from the coordinates (fertility against kinship) of the Sibly graph.

An innocent observer might well look at the line, say it’s zig zag and conclude it means nothing. But if you have followed this, you are not innocent. You know the truth. I’d not have done it for the world seeing what the knowledge has done to me, but we have an emergency and survival depends on having a lot of capable people working on this. As for me, there is no choice; the incubus is upon me.

Looking at it with your trained eye, you will at once break it down into three time periods. Over the first two hundred years the chance of survival rises steadily, as would be expected if there is selection.

Egypt lies along the Nile and setting up an administration is difficult. If you have a problem 20 miles upstream you don’t know what is happening on the other side of the rebellion. It takes a couple of centuries of shakedown to reach a good chance of survival. The Nile valley is a wiggly green bit in the midst of vast desert. The valley varies in width, sometimes something like 10 miles across. Of course, there is the delta, where the green expanse is much wider. At the edges, the land rises abruptly to the desert.

The river tends to be narrow and to run at the edge of the valley. None the less, you aren’t going to find marriage prospects in the river or out there in the desert any more than you’re going to find the king’s couriers. Your range of choices of mate is less along the river than in the delta, where on average you are a long way from desert.

This is the curse of the Nile. It is very difficult to set up a government, absent modern equipment, because of the difficulty communicating over enormous stretches of geography. So, for two hundred years we see selection, and survival rises because some groups may really be better at setting up an administrative structure and quelling descent than others are. Rising survival expectancy is the hallmark of selection that we have not seen elsewhere.

Over the next hundred years, there is the usual decline in survival that we found elsewhere. It seems truly wonderful that it crops up right on schedule. It even has that enigmatic curve that has been present before and looks quite clean, suggesting that for that century there isn’t any other process at work destroying dynasties.

And then something else remarkable happens. Survival goes through the roof. Throughout all of the thousands of years of history in this area three regimes broke through the three-hundred-year brick wall. No doubt they had some help from geography. For one thing, the rebels, too, would have had difficulty getting organized. But for another thing the restricted social choice caused by the geography looks like it meant that, in upper Egypt anyway, people tended to marry kin sufficiently often to produce an excess population, which could move downstream and repopulate the delta, which one would expect to suffer from infertility. The curse of the Nile has become a blessing of the Nile.

A third thing, a third blessing, again comes from the unique geography of the Nile region. If a regime is sufficiently oppressive, and I am only speculating mind you, the elite overlords have to give up one of their perks, to wit, the men picking up attractive young women for sexual pleasure. But if there is sufficient bad blood between normal and rich people, that becomes difficult. The young women hide, and wandering around looking for flesh gets dangerous. The would-be predators then have to deal with the geography, just like everybody else. Restricted social horizon gives long term survival. Just a thought from looking at the historical data.

I have mentioned the Foucault pendulum. You can find a book on it, although you might have to fish if out of the more numerous books by Umberto Eco or you can look it up on Wikipedia. What you will find, among other things, is the enormous care that must be taken to prove the world is turning using a pendulum which by and large rotates more slowly the closer to the equator. Setting it up is a labor by people who love the work. If errors are made, the movement of the pendulum may be so altered by spurious effects that it does not show the rotation at all. This to me is sort of iconic of science; things must be clean and exquisitely controlled.

Contrast this with a town in Lower Mesopotamia. I have no desire to offend, so if you live there, assume this is about the next town over. The stories I get from travelers is dust, people pooping in the street, camels with their notorious hard-biting flies and general activities that may baffle a stranger. If it is like the rest of the world, there will be people robbing and killing, people marrying and then cheating, corrupt officials, angry citizens, betrayals, conspiracies and other things you can probably imagine more of than can I. Yet when we look at the effect of birth rate in such circumstance, the evidence comes through loud and clear. Only kinship governs fertility. Everything else is fluff.

I find this totally amazing.